The Naming of James Blair, a History

How the school board's decision to keep the name of James Blair Middle School echoes a segregationist past

At this month’s work session, the Williamsburg-James City County (WJCC) School Board decided not to move forward with renaming James Blair Middle School. They chose to continue honoring Blair, a man who helped institutionalize slavery in Virginia, sending a message that Black students’ dignity doesn’t matter.

The school board preserved the school name despite the renaming committee’s recommendation to change it and months of testimony describing the horrors that Blair inflicted on the Black community.

This indifference to racial equality recalls the 1954 WJCC school board that named the school James Blair, the same one that doubled down on segregation despite the Supreme Court declaring it unconstitutional.

Understanding what the name James Blair represents today means going back to when—and why—it was first chosen.

The Blueprint for a Joint Segregated School System

The school named after James Blair began as a whites-only high school. Its construction marked the start of the new joint school division between Williamsburg and James City County.

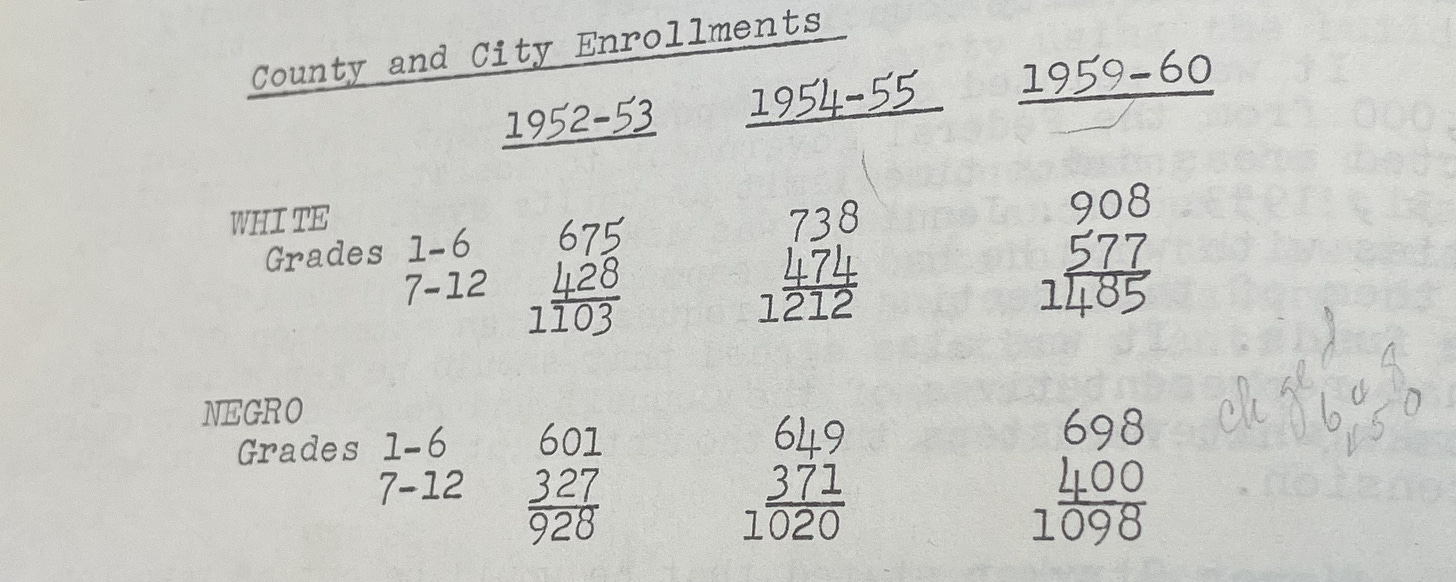

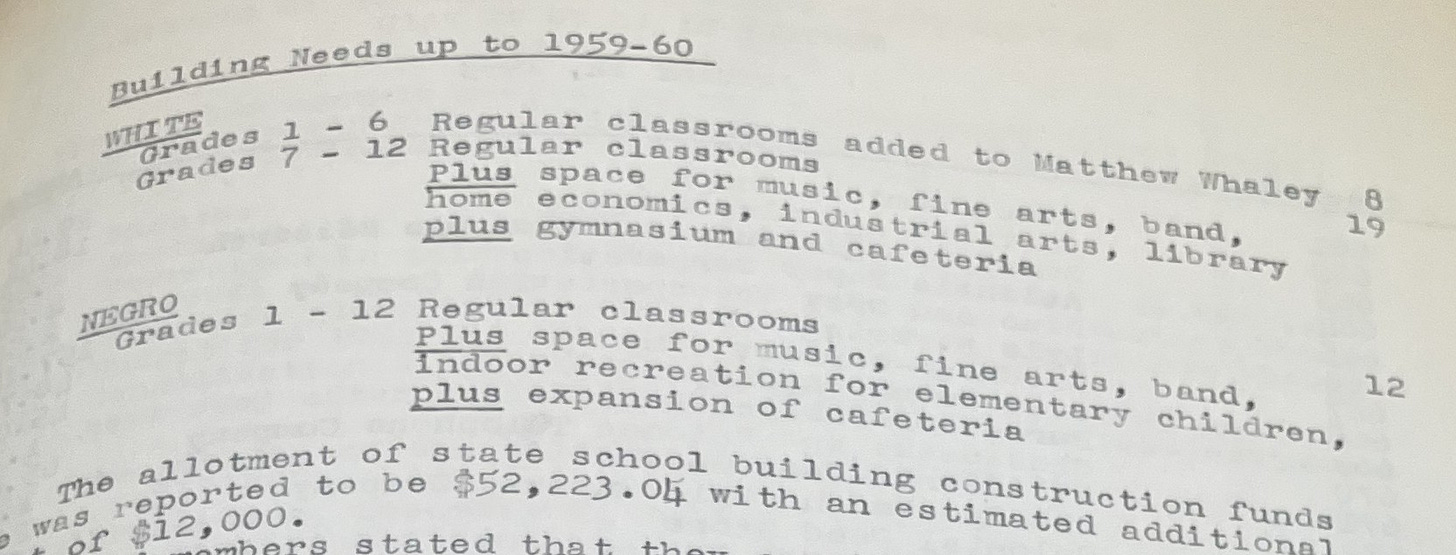

The plans for this segregated joint school division had white students attending the new high school and Matthew Whaley elementary, while Black students, first grade through high school, would be confined to one school, Bruton Heights. The rollout of this plan was overseen by infamous segregationist superintendent Rawls Byrd.

At the Dec. 10, 1953 meeting of the JCC school board, members briefly discussed naming the new high school for the first time. At the same meeting, the school board also reviewed an exchange between superintendent Byrd and a lawyer representing Black JCC citizens.

That lawyer raised the issues that Black students from the upper county would have to travel much farther to go to school under the new joint school division and that the current plans didn’t invest in Bruton Heights as much as the white schools.

Byrd had dismissed those concerns, saying that the county had voted for “a particular type of school consolidation” and that the unequal investment in the schools was due to there being fewer Black students.

Student population projections had allegedly showed 400 more white students by 1959, but at that time (1953) there were only 175 more white students than Black students.

Regardless, Byrd’s logic that more students justified more funding doesn’t explain why the division’s white schools were to receive higher quality amenities too, like a gym and a library, when the black school wouldn’t.

Earlier in 1953, Byrd had also responded to a letter from a “Mr. Whiting” who had requested that Byrd arrange a meeting between the school boards and Black citizens about building a new Black elementary school as part of the new joint school division.

In his response, Byrd used the excuse of public opinion to justify the unequal distribution of school resources, writing "the majority of county citizens do not want elementary schools in the upper end of the county."

Resisting Desegregation

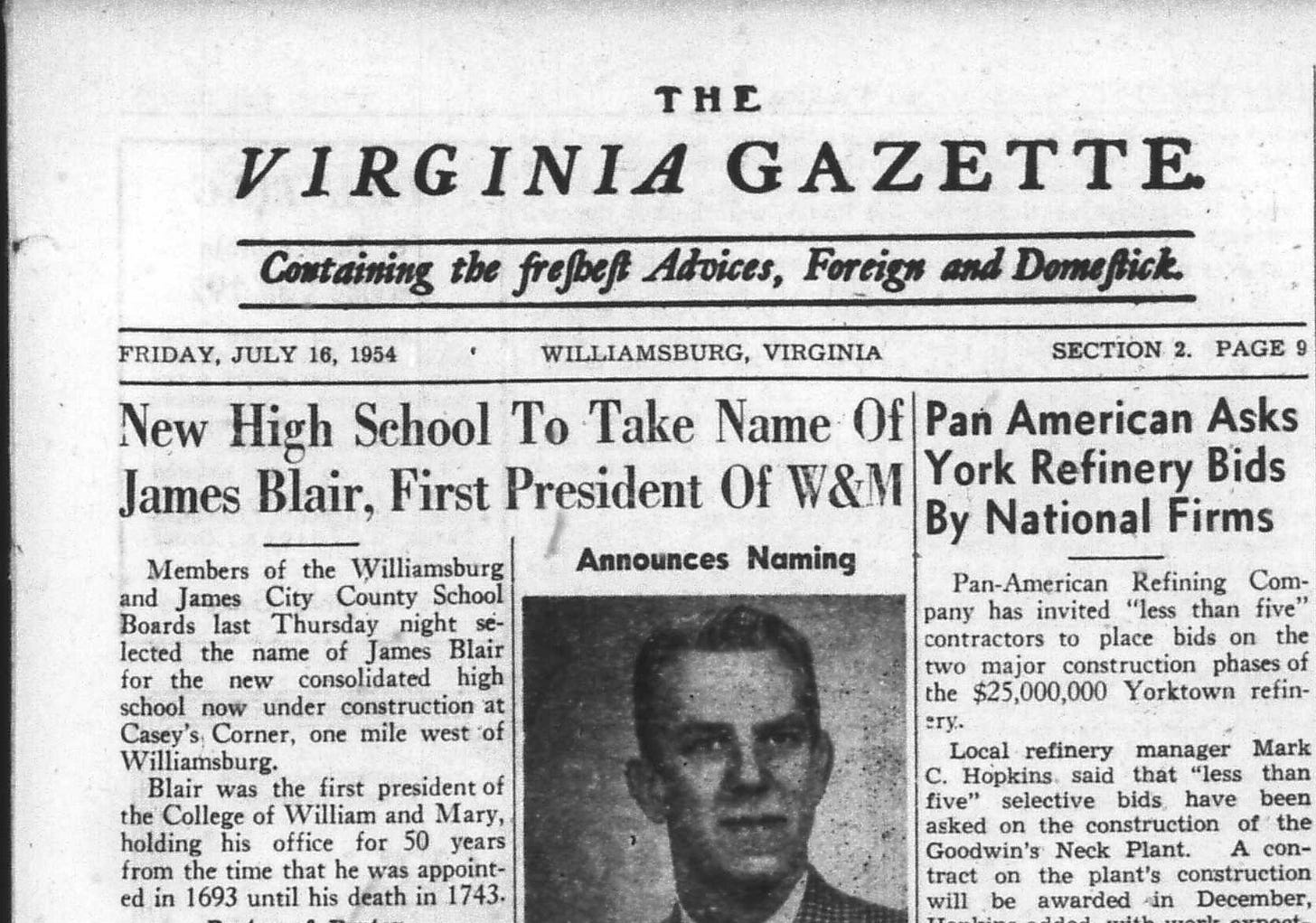

News that segregation had been ruled unconstitutional was the headline on the May 21, 1954 issue of the Virginia Gazette. In their coverage, the paper had asked Byrd for comment on whether the Brown v. Board of Education decision would affect the planned segregated WJCC school division. Byrd said that the school boards would take a wait and see approach.

Earlier that May, the school boards had formed a naming committee for the new high school. By June 14, name suggestions had been submitted, but the school boards postponed discussion, distracted by the Supreme Court ruling.

Byrd had put the question to the Williamsburg school board about whether to proceed with the plan for the segregated joint school division. According to the minutes, the board had stated that “they had no definite information to cause them to change the building plans already set up."

Byrd said that he had attended a separate meeting of Virginia school superintendents, where a majority of the superintendents believed the Brown v. Board ruling could be circumvented. Byrd said he doubted that was possible "even if such a course were considered to be a desirable one."

A few days later at the JCC school board meeting, members also discussed the "wisdom of awarding the contract for the additional construction at the Bruton Heights School" in lieu of the Supreme Court decision.

At that meeting, Byrd said it was possible for the allocated money to be used elsewhere but that "he had no information which led him to be sure that any one of the other schemes was a better risk then going ahead with the Bruton Heights expansion" and that "there was no immediate answer as to the plan that would be followed in Virginia and other Southern states."

The school board decided to award the contract and proceed as planned with the segregated joint school division.

The Naming of “James Blair”

On July 8, 1954, the Virginia Gazette reported that the joint division’s new high school would soon have a name. A requirement for the school name to be selected was that it represented "a colonial citizen of the area,” the article said.

At the joint meeting, school board members discussed the top proposed school names: John Rolfe, Alexander Spotswood, and James Blair. They would eventually vote in favor of James Blair, who "had a more direct influence on education than anyone of the several names suggested."

The naming committee concurred, writing "[Blair's] services to colonial education cannot be over-estimated."

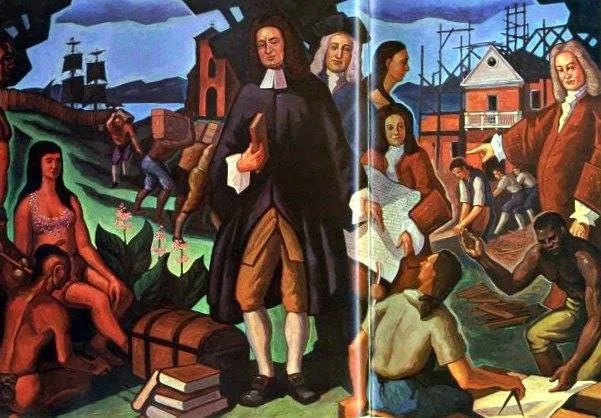

That influence on Virginia education, in Blair’s case, included loaning the College of William & Mary its first enslaved people and expanding the College’s investment in enslaved labor while he was president. Generations of black children were born into slavery to toil at the College-owned Nottoway Plantation, and the profits extracted from them would go towards white student scholarships.

The school boards didn’t mention Blair’s ties to slavery when they chose his name—but they were explicit in honoring his role in “colonial education,” a system that marginalized Black people and was supported by their enslavement.

Naming a whites-only school “James Blair” just weeks after Brown v. Board sent a clear message. It reaffirmed the racial hierarchy that Blair had championed, an educational system built on the suffering and exploitation of Black people.

The Push for Equal Education

In 1960, Black high school junior Lafayette Jones attempted to enroll at James Blair High School. Byrd, still superintendent, retaliated by calling Jones's father stating that if his son "did not rescind his request, his father-a carpenter - would never find work in town again."

At a Bruton Heights faculty meeting around the same time, Byrd reportedly told teachers that if Jones continued to try to attend James Blair, he would "shut down Bruton Heights and fire all the teachers."

Jones would graduate from Bruton Heights in 1961, recalling that Byrd said that "no black kid would ever go to that school," referring to James Blair. Byrd would enforce segregation for 10 years after the Supreme Court decision, and the first fully integrated class of 1969 would graduate only after Byrd retired.

On May 24, 2016, the WJCC school board voted to rename Rawls Byrd elementary school because of Byrd’s discrimination against the Black community and for his resistance to integration. Jones was a key organizer in the campaign to rename.

In a notable difference from the more recent school board decision, the 2016 board voted to change the name before conducting a survey.

“I think it’s really important not to delay on letting the public know, officially, that we very much support the changing of that name,” former school board member Jim Beers said at the May 24 meeting. “I think it’s appropriate for a statement.”

The 2016 board developed the policy for the naming and renaming of facilities in the WJCC school division that the Campaign for Honorable and Inclusive School Names referenced to request renaming James Blair Middle School in September 2024.

Renaming James Blair

This February, the current school board voted 5-1-1 in favor of looking into renaming James Blair Middle School based on our request. They formed a renaming committee, that committee issued a community survey, and when the results came back showing a slim majority opposed to renaming, board chair Sarah Ortego, along with members Kim Hundley and Amy Chen, reversed their earlier support. Or maybe they never supported renaming to begin with.

The 2016 school board had chosen principle over popularity when they removed Rawls Byrd’s name from the elementary school. Today’s school board did the opposite, justifying the unequal status quo by citing public opinion, just as Byrd had done when dismissing Black families’ calls for equal treatment 70 years ago.

But just as the decision to keep the name James Blair can be traced back to the racial prejudice of the segregation era, the Campaign for Honorable and Inclusive School Names takes inspiration from those who faced adversity to make our school division more equal.

We look to leaders like Rev. James B. Tabb, who would be one of the first to enroll his children at whites-only schools in Williamsburg. As president of the local NAACP, Tabb worked with the community across racial lines to make our school division fully integrated.

We also honor Mary Lassiter, one of our campaign organizers, and her classmates who were the first fully integrated class to graduate in Williamsburg, overcoming hardship to earn an education on par with their white peers.

And we’re following the precedent set by the 2016 school board, who understood that school names have meaning and that the school board has the discretion to show initiative when it comes to righting a past wrong.

We are disappointed that some of the school board members did not have the courage to follow through at this time, but our campaign is more resolved than ever to rename James Blair Middle School. We are committed to continuing public education on this topic, and in the upcoming election we will support school board candidates who have the moral conviction to stand for equality in education.